It may not be the most romantic of dates, but Perdido Key Beach Mice Duke and Bethany got a chance to briefly meet through their peanut butter jar carriers before moving into their new habitat together.

Editor’s note: This blogpost is the first in a series on the process of breeding critically endangered Perdido Key beach mice at Brevard Zoo, one of three zoos that have taken on this project. To read Part II (and see some beach mice pups!), please visit this link.

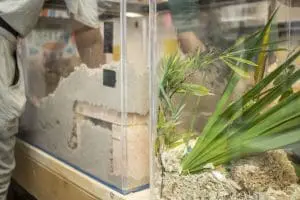

Step into a back room of our conservation department’s offices and you might hear and see some unexpected things. The shush of ocean waves comes from a sound machine. Tanks containing plants, hamster wheels, sand and the odd shell or two line wooden tables.

All of this sets the mood, so to speak, for breeding one of our Zoo’s most endangered residents: the Perdido Key beach mouse.

Key Creatures

Our Zoo is one of three Florida zoos carefully breeding these tiny (they weigh about 13 grams) and critically endangered mice that play a big part in coastal dune ecosystems in Florida and Alabama.

Perdido Key beach mice are one of seven subspecies that help spread the seeds of dune-stabilizing plants as well as aerate the soil to encourage the plant growth. This keeps the plants in place – preventing severe erosion.

Coastal development, feral cats, rising sea levels and hurricanes all threaten this species. Although the Perdido Key beach mouse was put on the endangered list in 1985, it wasn’t until 2004 – and Hurricane Ivan – that wildlife biologists removed 12 mice from Perdido Key State Park in order to protect the species. This action eventually kicked off the breeding project at Brevard Zoo in 2007.

Since then, 268 mice have been born at Brevard Zoo. Regular studies at Perdido Key keep track of the wild population. A reserve of mice also remains at the zoos in case Perdido Key’s population of beach mice decrease substantially – which has happened only once in 2010.

Conservationists look into a number of factors before adding mice to the wild population. A major hurricane may necessitate the addition of zoo-born mice to help the rebuilding process. Human development in the mice’s habitat may require a jumpstart of the population as well.

Every two years, conservationists bring in mice from their natural range to supplement the population at zoos.

“There is always surveying conducted prior to collecting mice to ensure that their numbers are strong. We are always extremely careful to be sure we wouldn’t be hindering the population by bringing mice back to the breeding program,” Mollie Lentini, the Zoo’s Conservation Manager, said.

Match.com for Mice

Zoo births are carefully planned for the good of the species – and Perdido Key beach mice are no different. A geneticist assesses each mouse brought to Brevard Zoo to determine which matches will ensure healthy, genetically diverse mice in this small population.

“The wild mice travel impressively long distances when they forage for food, so when we do collections we need to make sure that even though we picked two mice up in two different far-apart locations, that they aren’t related,” Mollie said. “We want to be sure that the mice we introduce to each other for breeding have never met before, and the geneticist helps with that!”

Once the mice arrive at the Zoo, they receive their own name, number and set of notches in their ears to help identify them.

A studbook keeper logs the numbers to help keep track of each mouse and its appropriate pair. The Zoo’s mice are kept in gender-specific tanks until after the geneticist makes his recommendations – and then pairing day begins.

At Brevard Zoo, 16 mice have recently been coupled up. These mice come from a recent permitted collection of wild mice by our Zoo’s conservation department staff from Perdido Key State Park, Gulf Islands National Seashore, and Gulf State Park. U.S. Fish and Wildlife technically owns all of the mice, and they are on loan to the Zoo as we care for them throughout the breeding program.

“It is a very long process to obtain permitting to house an endangered species, and the fact that we are allowed to house these mice at the Zoo speaks highly of the excellent level of husbandry and care for these animals,” Mollie said. “Permits are also required for transporting mice.”

This year’s pairs: Laird and Maya, Gidget and Corky, Sunny and Caroline, Duke and Bethany, Slater and Layne, Lopez and Lisa, and Dewy and Frida. Each pair moved into their own tank, which will be observed via video cameras for the next few months.

A Spritz of Saltwater

Trial and error led the Zoo to learn the ideal set up to encourage the mice’s natural instincts. The usual wood shavings found in the mice’s tanks is switched out for the sand mentioned above. A pergola-like concrete structure is placed in the bottom of the tank – under the sand – to give the mice a safe place to create a nest, which the mice can access through a hollow log.

Palm leaves, vines and other plants provide the materials the mice use to create a nest. A quick spray of salt water in the new habitat finishes it off.

On pairing day, each mouse is briefly placed in his or her own peanut butter jar (holes are of course drilled into the tops of the jar) and carefully identified via the notches in their ears. The two mates are placed next to each other to get a sniff of each other’s scent before being moved to their tank.

The mice often take a run around exploring the tank before getting to work. Within a day, the mice have started working on a network of tunnels that lead in and around their nest area.

These nests are made for sleeping and taking care of their future babies. The mice burrow into the sand at the right depth to ensure an ideal temperature and sand damp enough to hold its shape.

“The mice bring down leaves and palm fronds, and even feathers and sometimes snakeskin to cushion their nests – the scent from the snakeskin helps ward off other natural predators,” Mollie said. “The nests make a nice cozy spot for sleeping during the day and are a nice safe area for raising babies while they are nursing with mom.”

If all goes well, the pairs may start seeing pups by the start of the new year! Gestation takes about 22-26 days, and females can have 1-6 pups in a litter. Keep an eye out on our blog and social media channels for updates.

Thank you to Surfing’s Evolution & Preservation Foundation! Their generosity makes this critical conservation breeding program possible.

Brevard Zoo is an independent, not-for-profit organization that receives no recurring government funding for our operating costs. Your generous support enables us to continue to serve our community and continue our vital animal wellness, education and conservation programs.